The Importance Of Strength Training

Sprinters are built for power. It’s quite compelling to see how closely muscle mass correlates with performance on a bike. Quadriceps volume and cross-sectional area explain differences in crank torque (CT), showing a strong correlation with speed and power on a bike. Quadriceps muscle volume alone explains 76% of the variance in peak power output (PPO) during sprint tests. That’s a striking figure, and it comes as no surprise that strength training is such an important element in the development of elite-level sprint cyclists.

High levels of power are built in the weight room, which requires a well-balanced combination of heavy strength training and explosive lifts.

Heavy Lifts Build Strength

On one hand, heavy barbell lifts are necessary to build strength. Power relies on strength. Elite-level sprint cyclists lift two to three times a week with loads in excess of 80–85% of 1RM. This is required year-round to develop and maintain adequate levels of lower-body strength. Heavy resistance training is rarely discontinued, and volume increases as an athlete progresses through his or her career. Most elite-level sprint cyclists average around four to five sets of one to four reps at 80–85% of 1RM twice a week, alternating between back squats, front squats, and similar lifts.

Explosive Lifts Develop Power

On the other hand, explosive lifts are just as important for developing power, and this is where things get more complex.

Loaded jumps and plyometric training are sufficient to make the average athlete more explosive. However, elite-level sprint cyclists are not average athletes. It’s not unusual for a sprinter to have a 70 cm vertical jump with up to 60–70 W/kg of sheer power output. These figures are far above average and are only seen in sports like Olympic weightlifting and throwing. It comes as no surprise that one common factor among these athletes is Olympic weightlifting. Some of the best athletes on our team can clean 1.2–1.5 times their bodyweight, a number that would make them stand out even among competitive weightlifters.

Why Olympic Lifts Matter

Olympic lifts are necessary to build elite-level sprint power. Research has repeatedly demonstrated the benefits of Olympic lifting for developing high levels of power under heavy loading conditions. Isn’t that precisely what sprint cyclists need to go fast around a track? It’s all about generating torque at high cadence. In a flying effort, torque can exceed 200 Nm at 130 RPM. It comes as no surprise that modern sprinters often opt for bigger gears—the greater the torque, the greater the power.

Olympic lifts are a tremendous asset, but programming them is not as straightforward as it seems.

Optimal Loading Is Key

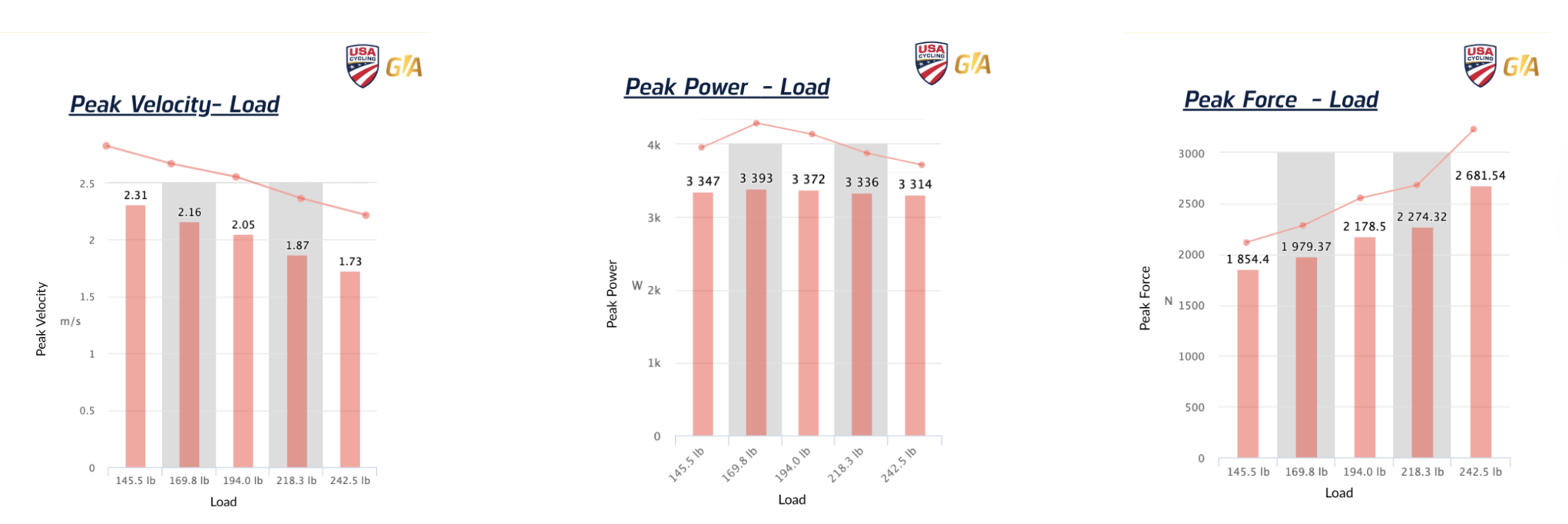

The concept of optimal loading is of paramount importance when it comes to all explosive lifts. In essence, optimal loading is based on the relationship between force, velocity, and power. Under heavy loading, bar velocity tends to drop, which substantially reduces the power an athlete can generate. Conversely, if the load is too light, bar velocity may skyrocket, but the absolute amount of power produced is very low. The load must be “just right” so that power output falls within a narrow range near its peak. That is the optimal load for training.

For most explosive lifts, such as loaded jumps, studies have shown an ideal range of loading conditions that correspond to the optimal load for power development. The review by Soriano et al. (2015) is highly recommended and can be very useful when programming explosive lifts. However, with Olympic lifts, things are more complicated due to differences in the kinetics and kinematics of various lifts. A snatch differs from a clean, a clean differs from a power clean, and a power clean differs from a clean pull. The list goes on. Luckily, technology comes in handy.

Utilizing Technology

GymAware RS and FLEX can measure the distance the bar travels during each lift. By connecting the unit to the bar, it is possible to calculate velocity and estimate the amount of power being generated. Peak concentric power output is one of the many metrics the app provides in real time. All it takes is testing a few different loads to see how peak concentric power output changes.

Starting at an RPE of 5 and performing sets of three repetitions, increasing the weight by roughly 10% between sets, peak concentric power output will increase until the load becomes too challenging to handle. The load corresponding to the greatest measurement of power is the optimal load.

Bar velocity and load vary depending on the lift. A power clean will have greater bar velocity but lower load than a clean. A clean pull will measure greater load but lower bar velocity than a clean. Once again, the list goes on.

Nevertheless, the procedure for identifying optimal load remains the same.

Programming Olympic Lifts For Sprint Cyclists

Most athletes can benefit from a variation of the main Olympic lifts—the snatch and the clean and jerk—once or twice a week, with three to four sets of one to three reps. Cleans are by far the most popular option and the one with which most sprint cyclists are familiar. There is no need to change lifts throughout the year, as long as the athlete is tested regularly to increase load when necessary. Heavy cleans are indicated in the off-season to increase strength and power, while hang power cleans are a more suitable option in the months leading up to a race. The lower load helps reduce volume as an athlete tapers for competition. This is the same approach we have successfully used with our athletes on Team USA, and the results have been impressive.

ABOUT GYMAWARE

GymAware delivers world-class velocity-based training (VBT) solutions and is widely recognized as the true gold standard. GymAware RS and FLEX enable coaches and athletes at all levels to measure and track strength training in the weight room. Trusted by elite teams, professional athletes, and researchers worldwide, GymAware provides highly reliable performance monitoring that drives smarter training and optimizes results across a wide range of sports.